I started the day where the Des Moines River empties into the Mississippi from the west and I ended the day (basically) where the Chippewa River does the same thing from the east. Along the way I do not know how many other rivers first from one side then the other fed the great river. And this is the story of the Mississippi River — it is not one river, it is the sum of all the rivers in the drainage. The Des Moines or the Chippewa may not mean much to you, but think about the Ohio, the Missouri, the Arkansas — these are rivers with entire histories across the east and west of our country and they disappear into the Mississippi. From Keokuk north to Red Wing Minnesota I rarely ventured far from the banks of the Mississippi. To the east, all day, were Illinois and Wisconsin and periodically, civilization got thicker around a bridge making a way across. My bartender in Keokuk, where there is a bridge to Hamilton, Ill., said when I asked if she was from Keokuk, “Oh no, I’m a Hamilton girl.” She’s worked at the same family owned, local Keokuk Iowa restaurant for almost 30 years (I ate at this place in 1988 when it was in the basement of the Iowan Hotel and she said she was volunteering as a busser then). She knows customers by name, calls their orders out to them before they open their mouths, looks, talks and acts like an Iowan. But she’s a “Hamilton girl.” If ever you needed an indication of the strength of the Mississippi River, there you have it.

It would be hard to imagine a better way to go north or south in the middle of the country than the Great River Road. I’ve been primarily on the western side, so I can’t speak for Illinois and Wisconsin, but Iowa and Minnesota are sublime. To me,for a good drive, there is kind of a magic mix among scenery, points of interest/towns, and open road. For the most part, the Great River Road ticks all the boxes very well. I spent 1987/88 traveling all 99 counties of Iowa, but I’d forgotten the northeast corner, which, for my money, is perfect. Hardwood forest, rolling hills and high bluffs, open ground, interesting towns along the way. I do wish the weather were better today. From dawn until 4:32 pm I never saw the sun. Most of the day it was raining. Until about 11:30, the fog was so thick I had no idea if I was next to the river or in it. I did catch a break around 11:30 when I got to the Effigy Mounds National Monument, just north of Marquette, Iowa and the rain stopped for period.

Located just inside the far western edge of the region generally associated with effigy mound culture, the national monument includes a north and south unit, miles and miles of hiking trails, and 206 known prehistoric mounds, 31 of which are animal effigy mounds. Historically, we know humans have been in this part of northeast Iowa for over 10,000 years; 2,500 years ago conical mounds appeared and were chiefly burial mounds; around 1,700 years ago, linear mounds appeared, but there was no evidence they were burial mounds, and some were connected to conical mounds forming what are known as compound mounds; the real art started about 1,400 years ago in the Late Woodland Period when the people in the Upper Mississippi began building animal effigy mounds. Most are bears, or birds. They are typically 2-4 feet high, 40 feet wide, and 80 feet long. But sizes, as they say, vary. What’s interesting to me, is that there is no ceremonial or ritualistic reason for them. There is indication in some that fires were set in the region of the animal’s heart or head, but no conclusive evidence that these mounds are anything other than what I would call yard art. Culturally, there is a link between the bear and the earth and the bird and the sky, so if you were an earth family, you probably built a bear mound mound and a sky family, a bird mound. To be honest, today, you can’t tell one from the other, or either from a small hill; but, back in the day, if you were looking at them from above, they were clearly birds and bears. Now how people 1,400 years ago got an aerial view of their handiwork, I don’t know, and, since from the ground level even then they didn’t really look like much, the mystery deepens. Nevertheless, when you climb the 2 mile trail to the top of the high bluffs over the river, through hardwood forests of Hickory, Oak, Cherry, Maple and Cottonwood and find, on the spine of the ridge amidst oddly clear green spaces, dirt bears, your skin kind of prickles. It’s a spiritual place for sure. Then, after 650 years or so, they stopped. No more effigy mounds. I suppose tastes changed, or the Joneses down the way made a pyramid mound and then everyone just had to have one or some such thing.

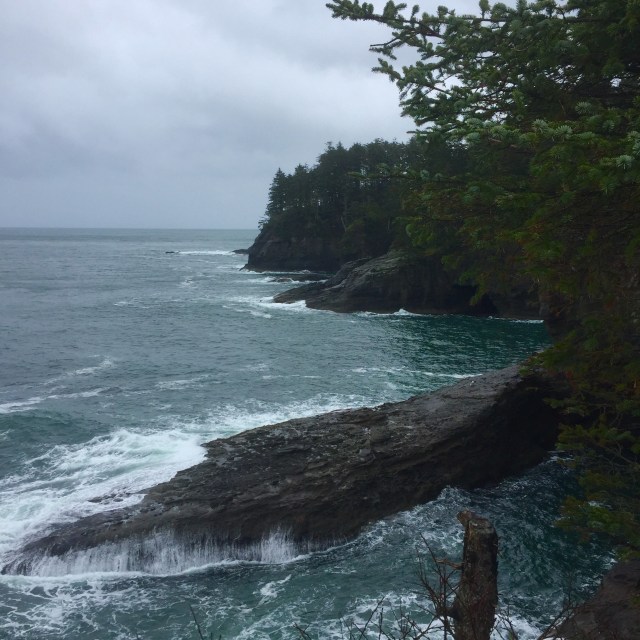

North of the Effigy Mound National Monument you are hard into the Upper Mississippi River, which is different primarily by constraint. On both shores, high bluffs hem the the old man in and efforts at man-made constraint — in the form of locks and dams — create pools and “lakes” that make it difficult to tell what is river and what is just lots of water. Above some of the dam and lock complexes, the Corps of Engineers has used the material dredged up from the channel to create man-made islands which they seed with native grasses. The result of this is that in the pool areas above the dam, a waterfowl paradise is born. The islands provide nesting and shelter area, and the slack water of the pool is excellent for feeding. Swans, geese, ducks and all manner of fowl have, thanks to the corps, their Eden. The effect of all of it — bluffs on each shore, the river banging first one side and then the other, the islands and pools and braided lakes on the slow side of the river — is really remarkable scenery.

Tomorrow the river turns west towards its source in northwestern Minnesota and I will as well. After a visit to the headwaters of the great river, I will finish the day, late I expect, where I last left the edge — in Grand Forks, North Dakota. From there the Fall installation of Edge Trek 2017 will really begin. North and east to the Canadian border with Minnesota, through the boundary waters region and on to Lake Superior. I don’t know how far I will get on Saturday, or care really. As I’ve learned already, the adventure is in the going, and I’m just getting started.